THE COURTAULD COURT AND CRAFT EXHIBITION AT COURTAULD GALLERY IN LONDON IS A MUST-SEE WHEN IT OPENS ON 20 FEBRUARY TILL 18 MAY 2014. ISLAM TENDS TO GET BAD PRESS IN THE WEST WHETHER IT DESERVES IT OR NOT BUT WHEN IT COMES TO ART, EVERYONE AGREES ISLAMIC ART IS BASED ON SHEER SKILL, DEXTERITY AND TALENT! USING GOLD, SILVER, COPPER, BRASS AND OTHER MEDIUM, THIS FORTHCOMING EXHIBITION WILL DEMONSTRATE ART (LIKE MUSIC) TRANSCENDS ALL BOUNDARIES.

The fabulous handbag circa 1300-1330 from Mosul, northern Iraq, height 15 cm and width 22 cm and depth 13.5 cm

The lid on the bag showing magnificent court scene of royal couple and retinue

The Courtauld Gallery

The lid on the bag showing magnificent court scene of royal couple and retinue

The Courtauld Gallery

Court and Craft: A

Masterpiece from Northern Iraq

20 February to 18

May 2014

For the first time in its history, The

Courtauld Gallery is staging an exhibition of art from the Islamic world.

Its centrepiece is one of the most beautiful works in the Gallery’s

collection, a brass container inlaid with intricate scenes of courtly life in

gold and silver, a masterpiece of luxury metalwork.

Despite its rarity and exquisite

craftsmanship, this superb object remains little known or understood.

Acquired by the Victorian collector Thomas Gambier Parry in 1858 and bequeathed

to The Courtauld by his grandson in 1966, this object was for many years

thought to be a wallet or document carrier, or even a saddlebag. The

exhibition proposes that it is in fact a handbag or, more properly, a shoulder

bag, made in the city of Mosul in northern Iraq

The Bag

The bag is likely to have been conceived

as an inlaid metalwork version of a luxury textile or leather bag. The 14th

century illustrations of the Il-Khanid court, pasted into an album in the late

18th century by a German bibliophile, Heinrich Friedrich von Diez,

depict such shoulder bags worn by the page of the Khatun, the wife of the

ruling Khan. Three of these folios will be on display. The

exquisite crafting of the Courtauld bag resembles goldsmiths’ work, and it is

possible that similar bags were produced in gold and even encrusted with

jewels. A bejewelled container of the same shape is held by one of the

attendants to the Chinese princess Humayun, as she sits in a garden alongside

her beloved Persian prince Humay, in a manuscript of poems by Khwaju

Kirmani. Transcribed in Baghdad

Detail of roundel with musician 1300 to 1330

The Court Scene

The inlaid decoration of the lid is the

bag’s most spectacular feature. Framed by a specially composed rhyming

inscription, bestowing praise and good wishes on the owner of the bag, is an

Il-Khanid court scene in miniature. Seated at the centre is a richly

dressed couple surrounded by a retinue of attendants in Mongol costume and

feathered hats who offer them food and drink and carry paraphernalia of a

princely life: parasol, falcon, lute. Beside the woman stands her page

holding a mirror and wearing, suspended across his chest, her bag.

Conviviality was at the heart of Mongol culture and this scene recalls

the festivities which took place after a day at the hunt. Images of a

noblewoman seated alongside her spouse in court scenes in manuscripts and, as

here, on metalwork, reflect the high status of women within Mongol society.

The scene follows the rectangular format of illustrations in manuscripts

of the period. This extraordinary image must have been designed especially

for the bag by someone well acquainted with the customs and costumes of the

Il-Khanid court, perhaps a painter of illustrated manuscripts like the small

Shahnama on loan from the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin.

A highlight of the exhibition will be a

life-size display recreating this lavish court scene and featuring objects

similar to those depicted: crescent-shaped gold earrings like those worn

by the lady, a Chinese mirror similar to the one held by the page, a Syrian

glass bottle as depicted on the table.

Gold earrings, 11th to 14th centuries from Nasser Khalili Collection

Syrian glass bottle or Mamluk Egypt, 1330

Enthronement scene from (detail) from Diez album

Blacas ewer 1232, brass engraved and inlaid with silver and copper

Spherical incense burner, Mosul, Iraq, 1319-1335, with inscription to Sultan Abu Sayeed

Humay and Humayun in the garden, from the Khamsa of Kwaju Kimani, Baghdad, 1396

Sultanah or noble lady walking with 2 attendants from Diez album, Tabriz, early 14th century, ink on paper

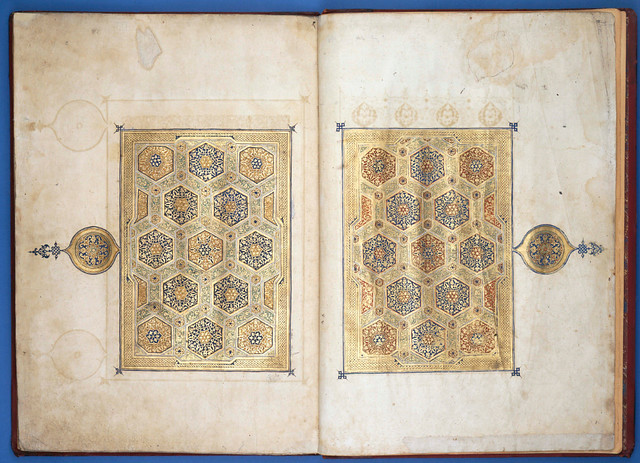

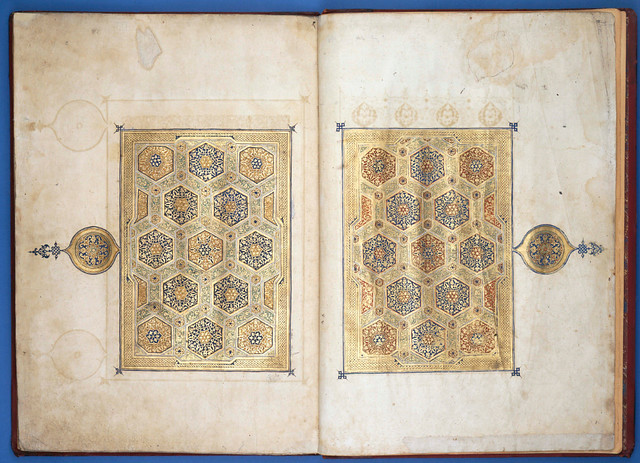

Koran written for the Sultan of Mosul, 1310, ink and gold on paper

Syrian glass bottle or Mamluk Egypt, 1330

Enthronement scene from (detail) from Diez album

Blacas ewer 1232, brass engraved and inlaid with silver and copper

Spherical incense burner, Mosul, Iraq, 1319-1335, with inscription to Sultan Abu Sayeed

Humay and Humayun in the garden, from the Khamsa of Kwaju Kimani, Baghdad, 1396

Sultanah or noble lady walking with 2 attendants from Diez album, Tabriz, early 14th century, ink on paper

Koran written for the Sultan of Mosul, 1310, ink and gold on paper

Trading Cultures

In the early 13th century,

the Mongol leader Chinggis Khan initiated a wave of invasions across Asia . In 1256 his grandson Hülegü established a

subsidiary dynasty, the Il-Khanids, to rule the south-western territories of

the Mongols. The Il-Khanids continued Mongol expansion into Anatolia and Iraq : in 1258 they captured Baghdad ,

the seat of the Caliphate, and in 1262, the city of Mosul China

The Il-Khanids were enthusiastic patrons

of art and architecture and their cosmopolitan court, which was peripatetic in

nature, was furnished with luxury objects from around the world: porcelains and

lacquer from China ,

silverwares and silks from Central Asia, enamelled glass from Syria

The encouragement and patronage of art

in Mosul under the Il-Khanids will be splendidly illustrated by two sections of

a celebrated copy of the Qur’an made for the ruler Öljeitü in 1310, as well as

a spherical incense burner created for Öljeitü’s son and successor, Abu Sacid,

on loan from the Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence.

Crafting Luxury: Mosul

An important section of the exhibition

will examine the inlaid metalwork tradition of Mosul Mosul

The Courtauld bag is richly ornamented

with roundels featuring musicians, hunters and revellers, over a geometric

fretwork pattern characteristic of the inlaid brass vessels for which the city

of Mosul was famous, such as the Blacas Ewer

from the British Museum Walters Art Museum in Baltimore ,

demonstrate that the technical and stylistic traditions of Mosul

Guest-curated by Rachel

Ward , formerly of the British Museum

No comments:

Post a Comment